NORTH AMERICA

NEW YORK CITYErmanno Wolf-Ferrari's Sly, one of the novelties of the 1927 season at La Scala, had a distinguished premiere there, with Aureliano Pertile and Mercedes Llopart in principal roles, Arturo Toscanini conducting and Giovacchino Forzano, who wrote the libretto, in charge of the staging. The fact that Forzano was a member of La Scala's management team eased the work's acceptance by the Milanese theater. Similarly, Plácido Domingo's eminence on the Met's roster was responsible for this opportunity to bring Sly to New York (April 1), in a production that originated (with José Carreras) three years ago at Washington Opera, of which Domingo is artistic director.

Sly in 1927 was less "modern" than several of its recent predecessors on the stage of La Scala, such as Pizzetti's Dèbora et Jaéle and Puccini's Turandot. Today, it sounds akin to Menotti. In subject matter, it overlays a stock Romantic preoccupation (the plight of the alienated artist) with a sprinkle of lately discovered neuroses (Freud had become fashionable). Though Wolf-Ferrari was half German, his stylistic preference was for the vernacular of verismo, rather than the twists and turns of Expressionism, which more venturesome composers were applying to similar subjects around that time. Strauss in Die Ägyptische Helena, Schreker in Die Gezeichneten and Zemlinsky in Der Zwerg all cooked with more paprika. But the staples of the stew remain the same: reality and illusion are fatally confused, while a perverse prank propels the plot and exotic trimmings garnish its stage picture.

The spark plug of the Sly story is a cruel trick played on Christopher Sly, an alcoholic poet in the Hoffmann mold, by the sadistic Count of Westmoreland, who functions the way Hoffmann's nemeses do in the Offenbach opera. In an elaborate charade, the passed-out poet is carried off to Westmoreland's castle, where he revives in a fairytale stage setting designed to make him think he's a rich lord recovering from years of amnesia. Sly is then thrown contemptuously into the wine cellar. As a literary conceit, it's fraught with intimations of deeper meaning, but on the realistic level, Forzano and Wolf-Ferrari had difficulty making their characters believably human. The Count is just another two-dimensional villain. His mistress, Dolly, functions as little more than a projection of Sly's craving for sympathetic feminine companionship. The title role calls out for something positive to assert. Unlike, say, Canio's jealousy crisis in Pagliacci, Sly's dilemma lacks gut credibility. Beyond a knack for amusing his friends, he has shown no signs of talent, and his creative suffering seems to consist entirely of terminal self-pity.

Wolf-Ferrari's music, piquant and emotional as a film score, is put together with professional fluency and security. He gives the singers plenty of free rein, building each act around an effective focal point -- Sly's ballad about a performing bear in Act I, his duet of awakening love with Dolly in Act II, his long monologue in Act III. The Met cast the work from strength. Domingo, deeply committed to the role, gave it his full range of mature resources as a singing actor. The tenor's clearly articulated voice and stage persona caught the tone of each act -- down and out in the first, confused but hopeful in the second, suicidally depressed in the third. He had a worthy partner in Maria Guleghina, whose strong, penetrating timbre, albeit with patches of reckless vocalism, conveyed passion and conviction. Juan Pons cut a satisfyingly nasty figure as Westmoreland, sounding out the role's arrogance, condescension and hypocrisy. Equally fine were Jane Bunnell as the harried Hostess of the Falcon Tavern and John Fanning, who strutted and fretted with a touch of old-fashioned operatic fustian as a Shakespearean actor, John Plake, ringleader of the tavern's literary crowd.

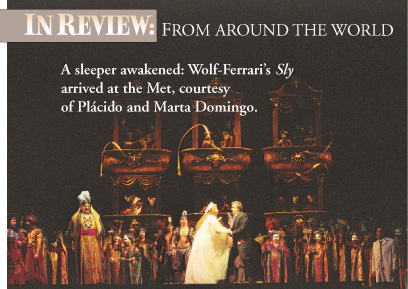

Plake's Shakespearean costume was the only link to The Taming of the Shrew, the (frequently excised) prologue of which suggested the Sly story to Forzano. Otherwise, this staging places the opera in the 1920s of its composition, though the locale is still London. The use of a scrim creates an appropriate sense of unreality, furthered by the darkness of the sets. Marta Domingo, the tenor's wife, in her Met debut as stage director, has shaped Sly in groupings and gestures as conservative and traditional as the work itself. Michael Scott's designs -- atmospheric in the dingy tavern, glitzy in the movie world of Westmoreland's pleasure palace, stark and semi-abstract in its wine cellar -- offered costumes as moody as his sets. He used redemptive white to single out Dolly in Act II and the Angel of Death (danced by Christine McMillan) in Act III. Marco Armiliato coaxed a full palette of colors from the orchestra, never letting things drag, phrasing gracefully, supporting the singers as Wolf-Ferrari knew well how to do.

JOHN W. FREEMAN