|

|

|

BUSONI AND REGER

The Egghead's "Gioconda

"Magazine article by Patrick J. Smith;

New Criterion, Vol. 19, March 2001

|

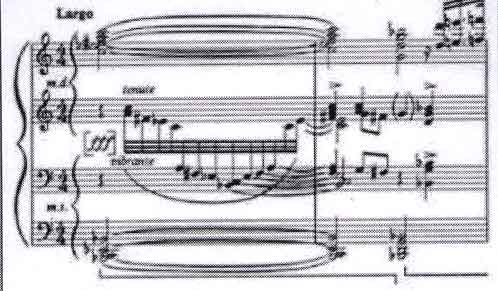

The two masters of the generation after Brahms mostly deeply impressed by Bach were Ferruccio Busoni ( 1866-1924) and Max Reger ( 1873-1916), the first a Germanized Italian, the second the most Teutonic of Germans. Neither was by any means free from romantic strains. [1] Busoni was a passionate admirer of Liszt; Reger's harmony is often hypertrophied to the last degree. Indeed their Janus-faces have given them an historical importance beyond that of their original creative powers. They met in 1895, became close friends and 'exchanged their compositions and piano-arrangements of Bach organ-works', [2] but to what extent there was any real mutual influence, it is difficult to determine. Both adopted the contemporary attitude to Bach, as a master who must be rescued from the dry-as-dust academics and presented to the public in contemporary terms with all the resources of contemporary instruments, an attitude which led to such inflated transcriptions as the conclusion of Busoni's piano version of Bach's organ Toccata in C major (BWV 564):

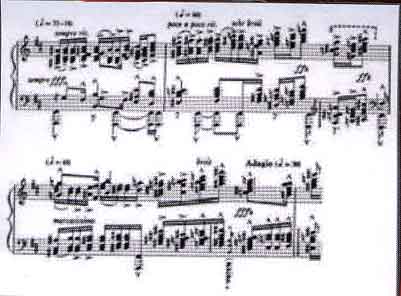

They naturally carried this monumental style of piano-writing over into original compositions in which they paid homage to Bach: Busoni Fantasia contrappuntistica ( 1910) and Reger Variationen und Fuge über ein Thema von J. S. Bach, Op. 81 ( 1904). Near the end of the latter, a double Monumentalfuge, [3] Reger presents both first (right hand) and second (left hand) subjects not simply combined but with typically thick harmonies:

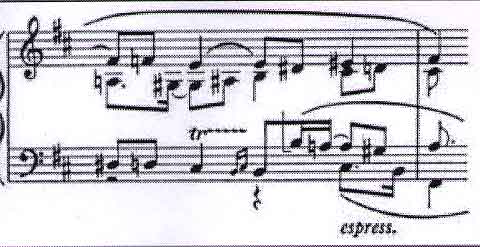

But an excerpt from the exposition will show Reger's genuine, if always rather harmony-bound, linear feeling:

a severe style which is maintained until the third section of the fugue and which represents the Reger who influenced his younger contemporaries, including Schoenberg. ('Schoenberg had always been interested in the music of Reger and had admired many things in it'; [4] when Schoenberg wrote of 'the great masters of our time' he habitually included Reger among their number.) Reger's sets of variations - Op. 81, the Beethoven Variations, Op. 86 ( 1904), the Telemann Variations, Op. 134 ( 1914) for piano, the Hiller and Mozart sets for orchestra, Op. 100 ( 1907) and Op. 132 (1914) - all end with fugues, as do a number of his other works, and nearly all, like Op. 81, with fugues whose dynamic plan reflects his own way of playing Bach. He would begin a fugue almost inaudibly and end with a triple forte; his own fugue in the Bach Variations begins pp (una corda) and ends ffff, and those of the Beethoven, Hiller and Mozart sets, after a mf or sfz call to attention, begin pp and proceed to a massive, heavily reined-in conclusion. There are highly romantic changes of tempo, and almost every entry of the subject is marcato in accordance with the common way of playing Bach at that period.

Not all Reger's very numerous fugues lean so heavily toward the romantic, though even the less monumental often preserve the basic conception of an overall crescendo. Near the very end of his life in the Preludes and Fugues, Op. 131a, for solo violin and Drei Duos (Kanons und Fugen im alten Stil) Op. 131b, for two violins ( 1914), he did achieve mastery of pure and classical line-drawing. Yet the lasting significance of Reger's copious fugue-writing lay not in his romanticizing of the fugue - he had begun, in the organ pieces of Op. 7 (1892) by imitating Bach without harmonic inflation - but in the fugal discipline he imposed on romantic music. Here the intellect reasserted its power to think in music rather than about music; and his later works in general, notably the Telemann Variations and the Clarinet Quintet (1916), recapture genuine classical feeling as well as classical techniques. This was no more than a personal achievement, however. It was reached too late to affect Reger's contemporaries, among whom classical feeling - balance and textural clarity, emotional restraint, and the other qualities commonly subsumed under the idea of the classical - was cherished by composers, particularly Ravel and his compatriots, who were little concerned with the techniques of polyphonic discipline and harshly intellectual harmonic schemes, and in any case knew nothing or little of Reger. (When Honegger went to Paris in 1911, 'féru de Richard Strauss et de Max Reger', he found the latter completely unknown there.) [5] On the other hand, those who were so concerned showed little sense of classical ideals, despite their increasing preoccupation with music and its technical devices for their own sake.

[1] 1 See supra, pp. 14-15 and 32.

[2] Fritz Stein, Max Reger ( Potsdam, 1939), p. 20.

[3] An apt term coined by Emanuel Gatscher, Die Fugentechnik Max Regers in ihrer Entwicklung ( Stuttgart, 1925).

[4] Dika Newlin, Bruckner-Mahler-Schoenberg ( New York, 1947), p. 275.

[5] Je suis compositeur ( Paris, 1951, p. 128; English translation by Wilson O. Clough, London, 1966)

|

|

|

|